Of Protestants and Catholics - Differences in Religious, Political, and Social Institutions

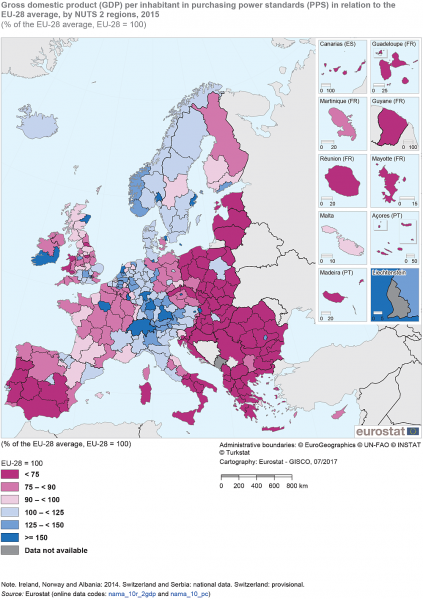

We can see the differences between Protestant Northern European countries (such as the Netherlands, Germany, the UK, etc) and Catholic Southern European countries (such as Portugal, Spain, and Italy) quite clearly in this chart (see below):

| |

| Eurostat 2017, accessed 10/29/2017 |

Protestant countries, by and large, chose to reduce the power and influence of the landed aristocracy and clergy. Without landed aristocracy and the Church hoarding wealth and influence, the Protestant nations' businesses were permitted and encouraged (often with state protection, authority, and support) to innovate, communicate openly, and exchange ideas and knowledge inexpensively for the time period. New technologies for the time were embraced, research was carried out, markets expanded and diversified with increasingly cheaper products, and wealth and status was (although very sub-optimally) distributed more widely. Political institutions were (again, sub-optimally) opened up for greater accountability and feedback.

The Catholic nations, meanwhile, reacted strongly against the Protestant Reformation, often with the support of the landed aristocracies and monarchs to quell unrest, innovation, and the introduction of new knowledge and information. Feedback and accountability for the nobility and the clergy were cut off, and those upper status groups lived high off the labor and effort of others' toiling in the fields. They chose to buy manufactured goods from other sources, or simply made do without them. Communication and assembly were discouraged, for fear of offending the monarchs, nobles, and clergy, and true innovation collapsed and was prevented from happening.

The proof of the different effects is in the effects it had, both in the short and long term, on each of the different spheres of influence. But societies and sides are dynamic, and yesterday's angels can become tomorrow's demons. The Capitalists of the Protestant North, supported by their more progressive and inclusive governments, may have been the defacto champions of equity, rights, innovation, and the public sector exerting its influence in the economy for their more broadly defined social interests. But it seems that the Capitalists have become quite like the landed aristocracies of old, complete with their own religious belief in the good of the "free market" to handle all society's affairs, such that they can be unencumbered for awhile from social, economic, and environmental obligations. They seem to have forgotten the political and social institutions that enabled them to get wealthy in the first place, and the need to maintain such pro-social, pro-environmental institutions to ensure they and others can get wealthy again, let alone, survive in the ecosystems we need to inhabit.

From this examination of a past example, combined with an observation from the current events and conditions my hypothesis is this:

Societies who adopt constant innovation, compassionate, pro-social, and pro-environmental governments, staffed with people who can be made accountable for their actions in government effectively with inexpensive, inclusive, and non-violent methods by the people who feel the effects of those decisions from government, will do better on average than those who seek to keep society in stasis for their own personal profit and gain.

This applies to the general society itself, such that the members of society who are outside of the government feel the positive effects from government, and become too capricious, economically, and socially greedy in their own rights (again, tomorrow's angels can become tomorrow's demons). It also applies to all levels of society, from the smallest of villages to the largest of nations. It is based on Darwin's observation that "it is not the strongest of the species that survives, but the ones most (effectively) responsive to change".

I also think that, for humans to survive and do well, we also need to have an element of abiding compassion and awareness within ourselves as individuals and as a group, such that we can check ourselves in our own lifetimes from creating more harm to ourselves and to others in the process of living. The evidence is growing that humans are not entirely selfish, individualistic creatures, but are in fact, very much social animals who depend on others for their survival, and in turn, reciprocate the help for others.

The proof of the different effects is in the effects it had, both in the short and long term, on each of the different spheres of influence. But societies and sides are dynamic, and yesterday's angels can become tomorrow's demons. The Capitalists of the Protestant North, supported by their more progressive and inclusive governments, may have been the defacto champions of equity, rights, innovation, and the public sector exerting its influence in the economy for their more broadly defined social interests. But it seems that the Capitalists have become quite like the landed aristocracies of old, complete with their own religious belief in the good of the "free market" to handle all society's affairs, such that they can be unencumbered for awhile from social, economic, and environmental obligations. They seem to have forgotten the political and social institutions that enabled them to get wealthy in the first place, and the need to maintain such pro-social, pro-environmental institutions to ensure they and others can get wealthy again, let alone, survive in the ecosystems we need to inhabit.

From this examination of a past example, combined with an observation from the current events and conditions my hypothesis is this:

Societies who adopt constant innovation, compassionate, pro-social, and pro-environmental governments, staffed with people who can be made accountable for their actions in government effectively with inexpensive, inclusive, and non-violent methods by the people who feel the effects of those decisions from government, will do better on average than those who seek to keep society in stasis for their own personal profit and gain.

This applies to the general society itself, such that the members of society who are outside of the government feel the positive effects from government, and become too capricious, economically, and socially greedy in their own rights (again, tomorrow's angels can become tomorrow's demons). It also applies to all levels of society, from the smallest of villages to the largest of nations. It is based on Darwin's observation that "it is not the strongest of the species that survives, but the ones most (effectively) responsive to change".

I also think that, for humans to survive and do well, we also need to have an element of abiding compassion and awareness within ourselves as individuals and as a group, such that we can check ourselves in our own lifetimes from creating more harm to ourselves and to others in the process of living. The evidence is growing that humans are not entirely selfish, individualistic creatures, but are in fact, very much social animals who depend on others for their survival, and in turn, reciprocate the help for others.

I do not know if anyone will hear of my hypothesis on how human societies can better evolve, develop, and adapt to present conditions. But it is at least observable that there are healthier and less healthy ways of managing human societies on a very broad and general scale. Hopefully some societies will learn in time to make the world better for themselves and others.

Sources:

GDP

at regional level. (2017, March). Retrieved October 29, 2017, from

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/GDP_at_regional_level

Iorgulescu, R. and Gowdy, J. (2005). The death of homo economicus. [online] ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46545372_The_death_of_homo_economicus [Accessed 29 Oct. 2017].

Iorgulescu, R. and Gowdy, J. (2005). The death of homo economicus. [online] ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46545372_The_death_of_homo_economicus [Accessed 29 Oct. 2017].

Comments

Post a Comment